|

NON-FICTION

Chris Arthur – Hidden Cargoes

This is a sharp collection of essays in which apparently trivial observations become a springboard into sustained reflection and philosophical deliberation. The opening piece focuses on an owl's skull, and the associations it's come to have for the author: he recalls the wood where he found the skull as a youngster, and ponders the nature of owls and skulls in general. The term 'kist of whistles' describes the skull's former contents, its network of veins, nerves and capillaries: it's an oddly apposite metaphor that deepens the more you think about it, the brain likened to a nest of organ pipes that come alive with the flow of air. This sense of deepening significance is common to all the essays, as Arthur artfully unpacks his subjects, probing them for meaning and insight. In ‘Ear Piece’ he focuses on the ears of two travellers occupying the seat in front of him on a coach; in ‘Voice Box’ a picture on a cigarette box triggers speculations about his father's love life; in ‘Letters’ the rediscovery of an old Scrabble set has him pondering the force of words, and so on. While the style is discursive, he manages to sustain his focus, peppering his essays with entertaining trivia. An immensely enjoyable book. Jenny Jefferies – For the Love of the Land

This is a book compiled by a selection of farmers who produce our food in the UK. There are forty in all, and one assumes there were forty in Part 1 – a heartening discovery amongst all the negative publicity about food production. The book is well set-out, with four pages devoted to each farm. Each one starts with a short piece written by the farmers themselves, detailing their personal history in farming and their philosophy towards their animals and crops. There are photographs of them on the facing page surrounded by pictures of their produce, livestock and land. On the next double page is the recipe, using ingredients from their own farms, followed by a mouth-watering photograph of the finished dish. It’s refreshing to see the farmers promote themselve: their beliefs in the high quality healthy food they produce and their innovative approach to high welfare standards. Many of them have won awards for their approach. A quick glance through the index shows the variety of food being produced – Breakfast Potatoes, Buffalo Lasagne, Droitwich Salt, Eco Ewe, Forest Fungi, Apple Cheese and Thyme Muffins etc. It’s a book which delights at every turn – excellent pictures of the farmers, beautiful landscapes, delicious food and practical recipes. Rod Madocks – Muzungu

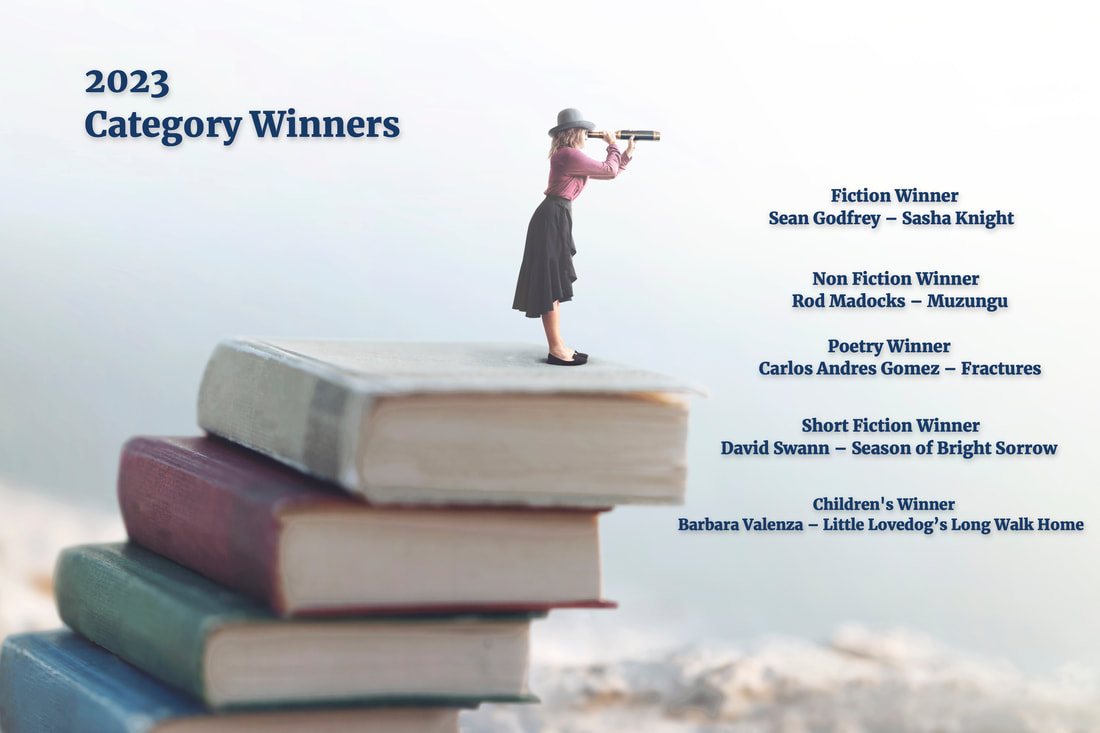

This is an intelligent and compelling memoir about growing up in Rhodesia in the mid-twentieth century. The title itself, Muzungu (slang for a white person, with connotations of purposeless wandering) offers a sense of how the country shapes the author’s identity: the legacy of his upbringing follows him to England, and endures throughout his life. Madocks describes his relationship with his parents, both of whom are drawn with sensitivity and skill, as are some of the staff who feature in his early life, most notably Jonas who re-enters his thoughts touchingly in the final passages. The book teems with interesting anecdotes, harrowing moments, and fascinating insights into local culture as Rhodesia moves inexorably toward independence. The fact that Madocks takes issue with post-colonial revisionist narratives might not be in tune with everyone’s opinion, but the author makes many worthwhile points. The second half of the book covers his life when he comes back to England, but there’s a lingering sadness that hovers over this section, and the reader comes to realise how the early years abroad have shaped and haunted his entire life. It offers us an understanding of how deep the roots of childhood penetrate, and how hard it is to adapt to a new country which is familiar to the parents but alien to the child. There is much to think about in this excellent memoir. Peter Street – Goalkeeper, Memoir of Poet Peter Street ed. Nema McMorran

This is a touching account of the poet Peter Street's childhood, particularly his struggle to understand and adjust to conventional life in mid-twentieth century Bolton. He can't work out why he's different, unable to fathom schoolwork, always missing the point of jokes, particularly those aimed at him. His only real talent is goalkeeping, and he looks set for a professional career until diagnosed with epilepsy as a young man. The book is written in a direct, often humorous style. He describes events with very distinctive figurative language, and his fondness for personification is unusual but effective. He says things like 'All the drums were gawping at me. The fifes were grinning'; this extends to descriptions of his own body 'My fingers became dizzy', not to mention his emotions, 'I walked away without saying a word, anger and ignorance shouting at me'. What initially seems like childish expression gradually becomes endearing as our understanding of Street's predicament deepens, and our fondness for him develops. It’s a lovely book about the traumas of growing up in a world ignorant of neurodiversity, told with more humour than bitterness. Mae Bunseng Taing with James Taing – Under the Naga Tail

A harrowing account of one man's experience of Cambodia's Year Zero, ghost-written by his son. The narrative moves quickly into nightmare territory as the implications of the Khmer Rouge takeover become apparent for Mae and his family. The horror of their five year ordeal and the contrast with their previously settled life is graphically presented. The history of the terrible events have been well-documented, but the chapters dealing with the shameful Thai response to the refugee issue are an eye-opener. The book is very readable, even with the relentless chronicling of so many horrors, and the strong sense of family permeates every page. It is remarkable and pleasing that so many of his wider family survived, although they have clearly been scarred by the loss of those members who didn’t, and eventually created a new life for themselves in the US. It’s a compulsive book, with much insight into the original Cambodian way of life, and it both fascinates and appals in equal measure. Mark Weston – The Saviour Fish

This offers a vivid and detailed description of the author's time living and working in a remote area of Tanzania, specifically Ukerewe Island, Lake Victoria. The writer soon loses his sense of alienation, and his treatment is mostly respectful and culturally sensitive. He makes it clear that he cares about the country and its people, and works hard to deepen the reader's understanding of their society and culture. It's mostly informative and entertaining, with some longer discussions of island history and politics. It is at its best where it has a human dimension, as in the account of Ali's illness, fishing with Hasani, brewing banana beer with Kitina, and the story of Lilian's life as a woman. There are some lovely insights into local culture too, tales of witchcraft and traditional healing, and the limits of medical care without access to accurate diagnoses. The author’s wife, Ebru, who lives with him on the island, is largely missing from the memoir, which means the reader observes through Weston’s eyes only. This means that book concentrates on his lack of knowledge when he arrives and the learning process as he gradually gains more insight, based largely on his reactions to events as he encounters them. An fascinating book about a part of the world that is not well known. POETRY

Carlos Andres Gomez – Fractures

This is a wonderful book, with a strong political focus. Race is a key theme, as in the excellent 'Underground', a poem about a woman forced to defecate in a field during the Jim Crow years. Gomez explores his own ethnicity in poems like 'Native Tongue', where he rediscovers his cultural roots through the language his father was reluctant to teach him, and 'Changing My Name', an assimilation fantasy where he imagines jettisoning his ethnic identity. He is commited to cultural progress, as in the poem 'Black Hair' which shows the speaker learning how to braid a woman’s hair, his effort to master the skill becoming symbolic of a desire to atone for generations of patriarchy. The responsibilities of fatherhood also feature in the book, particularly a desire to ensure a fairer world for children: in 'At the Playground, On the Bus, Everywhere' he hopes his daughter knows her ‘whole body is hers’; in 'Inertia' he is a ‘father tasked with suturing the fractured light’; in 'When Our Black Son Arrives', he anticipates waiting beside the front door for his son's return, ‘the first time/he takes the car out by himself’. It's a lovely collection by a poet who wants to make the world a better place, and it's certainly a better place for his book. Eamon Grennan – Plainchant

This is a wonderful collection of prose poems, presented as narrow blocks of text that act like arrow-slit windows onto the poet’s world. Mostly they’re observations of nature unpacked in language that brims with energy, like the hare he describes in his opening piece, ‘Encounter’: ‘Knacky keen and swift’ ‘agile as any fighter jet’. But unlike the hare, his poems don’t ‘knacky dash’ into ‘invisibility’; rather they linger in the mind, like answers to questions most of us don’t think to ask. He’s one of those poets who sees significance in the ostensibly trivial: a blackbird in a storm, a spider’s web, a swan’s ‘water-slapping wing-flaps’, a gannet ‘patrolling the tempest-tossed wind-blasted air’. Each poem proceeds with breathless momentum, building-up details to deliver one vivid and arresting scene after another. It’s a fabulous book worth revisiting many times. Oz Hardwick – A Census of Preconceptions

Hardwick’s prose poems are always worth reading, full of playfulness and irreverent surrealism. Anything can happen in his quirky world: in ‘Awayday’ ‘loose change’ transforms into ‘neon dragonflies’; in ‘At the City Gates’ ‘dreams flood out like dockers on bicycles’; the magpie he encounters in ‘After Class’ claims he’ll remember him, but doesn’t say why. In this respect the magpie is a little like Hardwick’s narrators - they never say why; mostly presumably this is because they don’t know, as is the case in by one of the best poems in the book, ‘The Museum of Silence’: here the speaker queues in the Museum shop, even though it stocks ‘stuff’ he already owns, ‘silently counting the coins in [his] pocket’. Hardwick’s book is supremely intelligent and full of insight. |

FICTION & YA

Mish Cromer – Alabama Chrome

This is a subtle and absorbing novel about coming to terms with loss. The point-of-view character, Cassidy, is expertly drawn, and while his story is unpacked with patience, it has more than enough momentum to keep us hooked. The narrative voice is assured and convincingly colloquial, generating a powerful sense of place, particularly in Levi’s Bar where Cassidy finds work: even the minor characters have presence here, and the barroom banter is deftly handled and authentic. Partly it's a novel about storytelling: it explores how stories can be misrepresented and exploited in our culture, particularly via the media (as with Brooke and her corny TV show, Random Acts of Kindness), but it also celebrates their potential to heal, connect, and liberate us, as Cassidy finds when he is able to unburden himself at the end. His relationship with Lark is nicely paced and engaging, and Cromer creates a happy ending without compromising the book’s emotional complexity. Sean Godfrey – Sasha Knight

This is an emotionally charged and visceral story set mostly in late twentieth century Jamaica. The narrator, Matthew, is a Seventh Day Adventist with a zealous mother and an absent father. As a child he finds companionship with the free spirited Sasha, whose mysterious disappearance becomes an obsession which threatens to consume him. She's a well constructed character, and Godfrey does a good job of keeping her in view as the past continually haunts the present. She's such an endearing presence that we feel her loss as much as he does, and the mystery becomes a very effective driver for the plot. The novel has a powerful vernacular feel, and the scenes in Jamaica are particularly vivid and immersive. They are also shocking - Matthew's world is governed by religious cant and violence, both at the social and domestic level. The church is marred by hypocrisy, and parental discipline feels like little more than socially sanctioned child abuse. Whilst offering an engaging account of Jamaica's vibrancy and natural beauty, the book exposes a toxic underbelly that’s as appalling as it is riveting. The novel succeeds brilliantly. Teresa Godfrey -Wipe Out

This is an intelligent and compelling novel offering an original take on post-pandemic dystopias. It’s a book that would appeal to both Adult and Young Adult readers. We see the world from the perspective of Hazel, a 'driver', who has no reason to question the system that controls everyone’s life until one of her team apparently commits suicide. We share her journey as this mystery is unpacked, and her world is gradually revealed in all its dark reality. When she meets Zac and Ethan, two subversives who try to enlighten her and persuade her to join them, the reader feels her dilemma. The mystery surrounding the Natural Births Experiment is handled adroitly, and believably. Human emotion is a key theme in the book: the cold, obedient Hazel is well-drawn in the early stages, and it’s pleasing to see her emotional life flowering, principally in her developing friendships, and also with the scenes in the Bio Med Centre. The novel raises worthwhile questions about the relationship between mother and child, and about consensus reality and our willingness to accept it. It works its way toward a satisfying climax as the team of subversives take on the New Citizen's Congress. It’s an excellent thriller set in a plausibly sinister future world. Eric S Hoffman – The Ballad of Clay Moore

This novel has a gripping opening, going straight into the action as a strange, unidentifiable aircraft lands on Clay Moore’s land. When he and his wife, Ashley, go to investigate, they find the pilot still alive, but all three of them only just manage to escape before the entire valley, including their home, is bombed. The story zips along at a furious pace from here. Hoffman's plot is wonderfully inventive. When Clay picks up a small stone from near the crash, he doesn’t initially realise its enormous significance, but it soon becomes clear that he is carrying in his pocket the key to limitless power and the potential to save the future world. He and his wife and the pilot are now pursued relentlessly by the people responsible for the crash, a sinister military group, who turn out not to be the US army. They pick up a wide range of characters on their flight across country and encounter several disasters as they head for the Greater Allegheny Gaming Convention, where they hope to confront Hobbes, the businessman who is the mastermind behind everything. On the way, Ashley gets captured and Clay enlists the help of his sister-in-law, Sage, an astro-physicist, for the final show-down. The narrative is so propulsive it takes your breath away, and the jokes fly as fast as the action. It’s impossible to not be hooked from the beginning as you race through the dialogue-driven scenes. It keeps the reader thoroughly entertained every step of the way. Abi Oliver – Letter from a Tea Garden

This is the story of Eleanora, a cynical, semi-sozzled 60 year old who’s invited by her young nephew, Roderick, to revisit India, the country of her birth. We learn about Eleanora's upbringing in early twentieth century India, her strained relationship with her mother, her father's suicide, and the mystery surrounding the disappearance of her brother, Hugh. In one sense the book is about the consequences of rejection and how this shapes Eleanora's adult life and character. She longs for a stable family and a sense of belonging, and, as the novel develops, she gradually finds ways of establishing meaningful connections with those who matter to her, including her nephew, his wife, and her old friend Persi. There's plenty of period detail, and the account of India is informed and interesting – there is a particularly interesting account of Calcutta during WWII, which is not generally known. There's clear evidence of research, but Oliver doesn't overwhelm us with it, handling the time shifts between past and present elegantly, and managing to build considerable suspense as Eleanora's story gradually unpacks. It has a 1960s perspective on colonialism, but the fact that we read it through a postcolonial lens adds another dimension to the book, particularly regarding the issue of belonging, and the relationship between place and identity. An extremely enjoyable and satisfying book. Jonathan Trigell – Under Country

This novel is a compelling coming of age story set against the social and psychological upheavals of Thatcher's Britain and the miners’ strikes. We follow the hero, Blue, from the mining community of his birth, to Margate, Skegness, and back in a propulsive tale brimming with intrigue and tension. The opening is dramatic - literally explosive - with consequences that echo throughout the rest of the book. When Blue becomes a ward of court we don’t quite know why, and this mystery is nicely handled, driving the story through various twists and turns to a conclusion that keeps the reader guessing till the end. The prose is strong, full of energy and lyricism, handling the world of the mining community and their language with impressive understanding. There’s a powerful sense of place - the descriptions of Blackmoor, Margate, and Skegness feel authentic, as does the opening pit disaster. Trigell’s account of the The Battle of Orgreave – a well-documented event - is impressive too, with an immersive, visceral quality. A very entertaining novel. |

|

Sarah James – Blood Sugar, Sex, Magic

This writer is clearly an accomplished poet. Many of the poems here are about the author's life as a diabetic, beginning with her diagnosis, learning to self-administer insulin, difficult conversations with the GP about life-expectancy, and the daily struggle to 'walk the tightrope/of balanced blood sugars'. These are interesting and informative poems, offering useful insights into the experience. While the theme of diabetes dominates, the book explores other subjects: it begins with a stunning poem about her lost sister, the poet's 'bones moulded to her absence', and there's some lovely verse about marriage, childbirth, motherhood, and general reflections on life. Despite the focus on illness, it's informed by a delightful optimism, as in poems like ‘My Still Life’, which closes, 'It starts with simple things; I open/the window and breathe in the sky ', or the beautiful poem, ‘Freshly Baked’, which closes, 'Time has taught me that memories too/should be softened and proofed.//Not all of my childhood was illness'. A lovely book which effortlessly turns trauma into art. Denise O'Hagan – Anamnesis

This collection addresses the extremes of human experience from birth to death. A mother's funeral provides the subject for 'Still the Rain Kept Falling', a beautiful poem in which the deceased comments on her own funeral proceedings, and which closes with a reference to the earth that is 'richer now for holding her': it's typical of O'Hagan's measured, reflective verse, expressing intense emotions with effortless fluency. Many poems are painterly in their descriptive detail, such as the excellent 'If I Could', where the speaker's desire to convey the wonder of the world to her child is set alongside her need to ameliorate the pain and insecurity of ill health ('the butterfly palpation trapped in your chest'). The poems are often concerned with memory and the process of retrieval: this is something she explores in the opening poem, 'Subtext', where significance is found in place, and the scrupulously observed minutia of the material world ('I'm talking of the dent in the hallway door/The cracked halo of paint around the handle of/The third cupboard on the kitchen'). O'Hagan's penetrating vision is such that she sees subtexts that the rest of us miss, and this makes for an exquisite collection that deserves its place on the shortlist. Emma Purshouse - It's Honorary, Bab.

This delightful book collects poetry produced by Emma Pursehouse during her tenure as Wolverhampton Poet Laureate: it's punctuated by prose pieces which contextualise the poems and offer a fascinating insight into the life of a jobbing poet - one made particularly difficult by lockdown. Part of a laureate's role is writing poems to order, and Pursehouse responds to her various commissions with impressive inventiveness, whether writing about allotments, social distancing, street talk, or the statue in Queens Square: she invariably brings humour, energy, and unpretentious intelligence to the task at hand. The final stanza of 'What's Great About This City?' includes the line 'We'm warm hearted and witty/we celebrate rough edges, the urban, the gritty', and this could stand as an accurate description of the book as a whole - humane, funny, and down-to-earth, it's clearly the work of a writer who loves her city, and who swims like a dolphin in the vernacular. Both the author, and Wolverhampton can be proud of this collection. CHILDREN

Kathy Creamer / Amy Calautti- Lucky’s Horse Shoes

A richly illustrated book for young children about Lucky, ‘the fastest horse in the stable’, who adores the ladies’ dresses and hats on race days. But when she falls in love with their shoes, she becomes determined to wear similar shoes, convinced that she will still be able to run the race. Unfortunately, all the other horses want them too. Predictably it ends in disaster and everyone accepts that horses need horse shoes for races. There are lovely, funny illustrations of horses in high-heeled shoes, and the story is told with clarity and humour, with a happy final message. Pam Henry – A Saucer Full of Secrets

The story is told by a white cat called Alban. He is found abandoned in the snow by a boy called Sedu, who takes him home to the monastery where he lives. When Alban sees him lifting objects without moving, it becomes apparent that Sedu has strange magical abilities and it soon becomes clear that Sedu and Alban can communicate with each other without speaking. Together, they hide on the monks’s boat, and travel to a strange island that gives them the opportunity to understand more about their magical gifts. They discover that they have to find four Treasures that were gifted to Mankind a very long time ago and return them. So they set out on a series of dangerous adventures. The story is based on Irish myths and legends, woven into a compelling and well-written book. It’s a fast-moving and unusual story. Jane Thomas/Rochelle Lamm – Silver River Shadow

This is a story based on events experienced by Rochelle’s own family, although it’s not apparent until the end that it is about actual events. Lizzie’s mother has died and she lives with her father, but when she finds photographs and documents in the attic, she begins to realise that there are many family secrets that her father has not told her. She and Bobby, the son of a neighbour, set off together to find out more. They cross the river to Canada in a canoe and head for a place called Grassy Narrows, where they gradually uncover the sinister facts about a scandal involving mercury poisoning and a local factory near where her ancestors live. They are rescued from disaster by members of the First Nation Ojibway community, who offer them generosity and explanations. A compelling read, it’s partly an exciting adventure story and partly a sobering exploration of the exploitation of a once thriving local community. Debra Tidball/Arielle Li – Anchored

This is a gentle story for very young children about separation. It shows the affection between a small tugboat and an enormous cargo ship – Tug and Ship – and Tug’s loneliness every time Ship sets off on a long voyage. Anyone who has seen how tugboats are used to guide big ships in and out of a harbour will appreciate the strength of their mutual dependence, so it makes a good illustration of how a small child can miss a parent when they go away for a while. The pictures are large and generous as they follow Ship across the world’s oceans, the text is clear and well set out and the message that Ship always returns is one of comfort and reassurance. Dawn Treacher – Pandemonium of Parrots

This is a wonderfully imaginative story for older children about Otto, an orphan. He lives with his uncle, a bad-tempered inventor who builds mechanical animals in an Orangery, protected from the outside world, where he never goes. One day he meets Florence, a street urchin who has managed to find a way into the Orangery. But when the Orangery is broken into and the mechanical parrots are stolen, she is the one who gets the blame. Otto and Florence join forces to find out who is responsible, helped by a gang of street urchins, friends of Florence. There are pirates, a remarkably clever mechanical monkey, strange lands and mysterious characters who are not who they seem. It’s an exciting adventure story full of fun and excitement. Barbara Valenza – Little Lovedog’s Long Walk Home

This is a delightful picture book about a sausage dog who can’t find anyone who will come to his party. The other dogs laugh at his strange shape when they are invited, so he goes home alone. But on the way, he meets various characters who need help and he offers them all a ride on his long back. When he arrives home, they have a wonderful party together. There are many pleasing little touches which add to the magic of the book: the illustrations are clear and immediately appealing; the text is short and skilfully simple, well-suited to young childen; the pictures stretch from one page to the next, sometimes even requiring a page turn; a little yellow dog appears regularly as an observer, without ever taking part in the story. And the overall message about true friendship is a sweet one. |

SHORT FICTION

Douglas Bruton – With or Without Angels

This is an unusual book inspired by the artworks of the late Scottish painter Alan Smith, which were themselves inspired by Il Mondo Nuovo (The New World) by Giandomenico Tiepolo. It addresses Smith’s initial encounter with Tiepolo’s painting in Venice, and explores how Smith reworks the image in later life, taking elements from the painting and incorporating them in new work. Smith was in the late stages of a terminal illness at the time, so he is working against the clock, helped by a mysterious young artist called Livvy who becomes his ‘hands’. I like the concept behind the book - in some ways it takes ekphrastic writing to a new level, building a fiction around the creative process and unpacking some of the ideas that underpin Smith’s work, including change, mortality, perception, and the significance of influence and intertextuality. It is extremely readable - the narrative is fragmented, but Bruton’s prose is fluent and lucid. The book is absorbing and satisfying. Tim Craig – Now You See Him

This is a superb collection. Craig has a wit and sense of the absurd that lends itself perfectly to micro-fiction. Many of the stories are ‘electric’ in the manner of the cat from the opening piece, ‘Cat Barbecue’: you feel a charge of energy in their presence, and they have a depth and beauty that can be simultaneously captivating and unsettling. Some, like ‘Parts of My Mother’, where the speaker’s mother begins to fall apart, or ‘Falling Silent’, where people kill birds by banging pots and pans together in the street, have a surreal dimension reminiscent of micro-fiction masters like Dan Rhodes. Each story demonstrates how to capture the essence of an individual in few words: the father in the title story, ‘Now You See Him’, whose final disappearance reflects an inability to confront emotions; the individuals in the doomed lift in ‘Going Down’ (which has a very funny conclusion despite the grim inevitability of their situation); and ‘The B of the Bang’ which remembers an extra in North by Northwest, speculating as to whether he’s spent a lifetime anticipating shocks, just as he apparently anticipates Eva Marie Saint’s gunshot in the movie! It’s a delight to read. Annalisa Crawford - The Clock in My Mother's House and Other Stories

There’s a hint of darkness in the background in of the stories in Crawford’s collection, and the creepy atmosphere which pervades most of them demonstrates her obvious skill at creating uncertainty and menace. The title piece sets the tone with its gesture toward the paranormal as time starts to move backwards and the mother starts to shrink. In 'A Thousand Pieces of You', a smashed mirror reflects the protagonist's disintegration; in 'Click', a camera becomes a repository for the speaker's emotions; in 'One Minute Silence', an inventive countdown-structure frames a tale of an exploding hotel. 'All the Magpies Come Out to Play' with its sinister birds, and the closing story, 'Adventures in My Own Back Garden', about a guy trapped in the garden following an accident are thoughtful and touching. The stories are fluent and imaginative, always diverting the reader away from the pathway of normality into the unexpected. Rebecca Lawton – What I Never Told You: Stories

The title story, addressed to a deceased Vietnam veteran, is richly textured, offering a vivid portrait of the narrator’s traumatised lover and the effects of PTSD. I enjoyed it very much, and it sets a high standard. The second story, ‘Sipapu’, is impressive too: the protagonist, True’s, desire for a child is validated by her encounter with a Native American family in a story that locates parenthood at the heart of human values. Lawton writes beautifully about the natural world, particularly rivers, as in ‘Seven Pieces of Pineapple’, ‘Only Water’, and ‘A Real Cafe’, where it provides the backdrop for the relationship between Mare, a recurring character who works as a river guide, and Jack. Mare crops up again in ‘Gravity’, which is also laden with water symbolism, and there are several linked pieces where Mare reappears. It’s an excellent book, introducing the reader to a tough natural world which may not be familiar to them. JK Mazelis - Blister and Other Stories

In ‘The Winter Child’, a boy reads fairy tales until his life comes to resemble one: it's very creepy and atmospheric, deftly recycling tropes from folk narratives - stolen mothers, princes, sinister woods, etc. As a story about the dark, corrupting potential of stories, it works wonderfully well. ‘The Tower and the Mountain’ has a similar theme, where the speaker struggles to reconcile inherited narratives with her experience of the world. Again, this is a thoughtful piece. Some have the feel of Robert Aickman tales, with gestures towards the uncanny - an example is ‘The Famous Man’, where a critic interviews an author who, for reasons best known to himself, insists on hiding behind a curtain for the duration. The tale has good momentum, and I enjoyed the oddness of the writer and his naked assistant. Again, the piece is heavily intertextual, referencing ‘The Red Shoes’ - it picks up on the violence and repressed sexuality that informs tales of that kind. The title story is also excellent - the author captures the child's point of view expertly, and I love the way he attempts to take control of his world with his ray-gun: he's another character whose understanding of reality is shaped by the stories he inherits and half believes. Excellent. David Swann – Season of Bright Sorrow

This is a lovely novella-in-flashes which really gets the most out of the form. It was entered as a cross-over between Fiction and Young Adult, and could easily be read and enjoyed by both sets of readers. Many of the flashes would work as discrete pieces, but they are strengthened by a narrative integrity that attests to Swann's skill as a short-form writer. Together they build into a touching tale of a young girl trying to make sense of the world. His account of the down-at-heel coastal town where she resides with her alcoholic mother is superb: ‘it punches you in the face. All that space and air.’ Lana's limited perspective is a source of much gentle humour, but also tension as we watch her struggle with home life, school, and the bleak landscape of the bay, which almost becomes a character itself. Swann possesses an ability to create living, breathing people out of very few words, a skill that many writers would envy: the landlord, who has a ‘shifty-looking stoop’, with his fixation on power-points: Lana's school friend, Archie, with his tendency to talk 'mince'; and of course Lana herself, who lies at the emotional heart of the book. There is a strong sense of her loneliness and fear which pervades the book, as she negotiates her way through hardship, deprivation and uncertainty, but she still manage to produce witheringly ironic exchanges with Archie. She tells her sympathetic teacher that she likes the beach and the sea. “Then you’re in the right place, lass.” In many ways, this sums up the deceptively simple and profoundly complex themes of the book. |